In a time of growing online violence, women in tech are leading the advocacy and work on developing safeguards and accountability systems to protect female users. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, it was largely women in medical research who led the development of vaccines while also studying gendered impacts of COVID-19 on women’s bodies – a nuance which is too often excluded from scientific study. Closing the gender gap in STEM will ensure that women have access to more high-skilled employment and are meaningfully included in the economic growth that is driven by technology and innovation.Īt the same time, as these fields evolve and expand, it is increasingly imperative that the capabilities and perspectives of women are brought in to bring about innovative inclusive, and effective solutions to the complex societal challenges of today and to strengthen our collective performance on economic and development indicators.

Women in Sri Lanka’s workforce predominantly belong to the low-skilled and informal workforce, and continue to be a minority in sectors like the tech industry, for example, which is one of the fastest-growing and highest-paying sectors worldwide. With an increasing number of jobs being digitalized, it is essential that women are not left behind in this transition and contribute to the development of a more equal and sustainable future economy. Building off of harmful gender norms and biases, economic hardship has affected girls’ access to education, with families choosing to educate their sons instead of daughters to cope with rising costs and poverty.Īs Sri Lanka navigates this economic crisis, addressing the gender gap in STEM fields is more crucial than ever.

In Sri Lanka, the multilayered crisis threatens to widen the gender gap in STEM fields. These are major challenges to women's equal entry into and engagement in STEM careers. Men – particularly male family members, educators, and employers – allow these norms to guide their support, teaching, and recruitment. Women often choose their fields of education and work based on how they perceive their abilities and roles in society. These biases and norms affect men and women in these sectors.

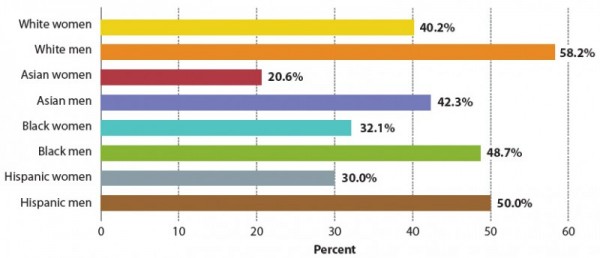

These range from the idea that investment in women’s education is less important since women are primarily caregivers while men are breadwinners, to the belief that certain STEM fields are naturally more suited to the ‘male/ masculine’ mind and that women cannot equally understand or thrive in them. The underrepresentation of women in STEM is shaped by harmful gender stereotypes, norms and roles. Why are there fewer women in STEM fields? There is also a significant gendered divide within different STEM sectors, with much lower representation of women in fields like math, engineering and technology which are seen as ‘masculine’ or ‘male oriented’ fields, while more women in STEM pursue care-oriented fields such as health and biological sciences. And yet, when examining the workforce, there are far fewer women working and leading in STEM. How serious is the underrepresentation of women in STEM in Sri Lanka? According to the University Grants Commission (UGC), in 2017, women accounted for nearly half – 49 percent - of undergraduate enrolments in STEM subjects in local universities. Did you know that globally women amount to only about a quarter of the workforce in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM), and that men vastly outnumber women majoring in most STEM fields in universities? The gender gaps are particularly high in some of the fastest-growing and highest-paid jobs such as IT and engineering.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)